|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 32 Page 15 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links | Print this page |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The TSR-2: A BRITISH STORY WITH AN AUSTRALIAN CHAPTER

With the era of the F-111 coming to a close, it is timely to reflect on

the development of this aircraft and the rivals that existed at the time

of its selection. The principal competitor was the British Aircraft

Corporation’s Tactical Strike and Reconnaissance (TSR-2) aircraft.

However, as indicated by Sir Sydney Camm’s comment, the development and

subsequent abrupt cancellation of the project in 1965 was politically

charged

From the mid 1950s, the RAF and subsequently the RAAF identified the need to replace the Canberra bomber, focusing on a nuclear-capable aircraft. Given the rapid advances in anti-aircraft weaponry capability, having supersonic strike aircraft that could slip under radar surveillance was seen as a priority. The development of the TSR-2 was also the result of the British Government’s focus in the late 1950s on rationalising the eight main British aircraft manufacturers that then existed. On New Year’s Day 1959, Vickers-Armstrong and English Electric, amalgamated as the new British Aircraft Corporation (BAC), were awarded the contract to combine their earlier individual designs into the TSR-2. Later that year Bristol-Siddeley were awarded the contract for development of the Olympus engines which were to power the aircraft.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Like the development of any aircraft, the TSR-2 had its technical problems. In late 1964, three completed prototypes had made it off the production line and the maiden flight was undertaken from Boscombe Down. A three-month delay between the first and second test flights occurred, due to the engines on the aircraft not being up to speciations, trouble with the undercarriage, and fuel pump oscillation that led to cockpit vibration at the same frequency as the human eyeball which affected the vision of the pilot.

While these were not minor problems, two other factors of greater import arose that sounded the death-knell for the TSR-2: a change of government, and projected costs. The newly elected Labour Government, which promised defence expenditure cutting measures in its election campaign announced in the 1965 Budget that the TSR-2 was cancelled ‘forthwith’ and the remaining aircraft on the production line were sent to scrap merchants.

It is said that the melted TSR-2 parts went on to serve the nation as washing machines.

It was also claimed that the British Labour Party and Treasury officials believed that America would provide the UK with F-111 aircraft at an fixed price, something that BAC could not offer, and this would amount to a saving of 300 million pounds over the TSR-2. The UK took out an option on 24 F-111s to be in service by 1967 but once this order got caught up in the same delivery delays that Australia experienced the commitment was cancelled.

These decisions made the British aircraft industry feel abandoned by their own government, which failed to appreciate the advanced sales methods of the Americans and also that in many cases the US adopted aircraft production techniques that were developed in the UK.

Australia had expressed a high degree of interest in the TSR-2 when the TFX (later to become the F-111) was still on the drawing board. While the majority of Australia’s air force budget from 1959 to 1965 was devoted to the purchase of the Mirage III, Australia was actively canvassing for a bomber replacement.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

“All modern military aircraft have four dimensions: span, length, height and politics. The TSR-2 got the first three right.”

Sir Sydney Camm (1893-1966), Chief Designer, Hawker Aircraft Ltd

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

In August 1960, the Commonwealth Chiefs of Staff were briefed on the

TSR-2 which had a marked effect on

First, the UK Ministry of Defence turned down a suggestion by BAC that the later stages of the flight program involving terrain following and weapon delivery should be carried out at Woomera. Second, in April 1963 Scherger went to Paris for a SEATO conference and paid a short visit to London during which he met with Lord Mountbatten, the UK Chief of Defence Staff. Mountbatten expressed doubt that anything would come of the TSR-2 project on the grounds of cost and complexity, and made it clear that he was arguing in favour of the Buccaneer aircraft over the TSR-2. Australia eventually purchased 24 F-111A's, which had even greater development problems than the TSR-2 and eventually ended up costing far more than the TSR-2 would have done.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Whatever hits the fan will not be distributed evenly.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

In many people’s eyes, the UK Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) Lord Louis

Mountbatten, was an over-promoted charlatan, who was possibly the worst

CDS ever to hold that office. Mountbatten, who was

killed in an IRA bomb blast in August 1979, allowed his own biased

opinions to over-rule any reasoned argument was and

In his book Murder of the TSR2, Stephen Hastings, a decorated World War II army officer and Conservative MP (as well as a director of aircraft company Handley Page), claims ‘that three and half years of painstaking promotion, technical explanation and sales preparation during which a seemingly impregnable position had been built up by BAC, were dissipated overnight’.

On Scherger’s return to Australia, in May 1963, the Australian Government announced that they had authorised the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Sir Valston Hancock, (left) to evaluate the Canberra replacement. He decided to consider the French Mirage IV, the British TSR-2, and the US Phantom and Vigilante, in that order. At that point the F-111 did not feature on the shortlist. When Hancock visited the UK, it was suggested that V-bombers could be provided to Australia as an interim arrangement until TSR-2 deliveries were made. However, this offer was conditional upon the force being both crewed and under the command of the RAF a proposal that clearly did not appeal to the Australian Government or the RAAF.

Another telling shortcoming in the TSR-2 development process was that BAC did not receive a firm order from the UK Government for 21 development and reproduction TSR-2 aircraft until shortly after the Australian decision to order the F-111 in October 1963. After that, the TSR-2 project did not gain sufficient momentum and was finally ended by the fateful Labour Government decision.

Today only two TSR-2s remain. One (XR 220) is at the RAF Museum at Cosford and the other (XR 222) at the Imperial War Museum, Duxford. The only TSR-2 to .fly (XR 219) and two un-finished air frames (XR 221 and XR 223) were used as gunnery targets. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The haste with which the UK Labour Government made its decision has been the source of argument and bitterness and the subject of numerous magazine articles, books and even a TV documentary.

It was a sad, sorry saga of the destruction of what could have become one of the great aircraft of the 1970s and 1980s.

The F-111 has served Australia well, but had it not been for a combination of factors Australia might have been farewelling the TSR-2 in 2010.

Aircraft Specs:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

A golfer is in a competitive match with a friend, who is ahead by a couple of strokes. "Boy, I'd give anything to sink this putt," the golfer mumbles to himself. Just then, a stranger walks up beside him and whispers, "Would you be willing to give up one-fourth of your sex life?" Thinking the man is crazy and his answer will be meaningless, the golfer also feels that maybe this is a good omen so he says, "Sure," and sinks the putt.

Two holes later, he mumbles to himself again, "Gee, I sure would like to get an eagle on this one."The same stranger is at his side again and whispers, "Would it be worth giving up another fourth of your sex life?" Shrugging, the golfer replies, "Okay" And he makes an eagle.

On the final hole, the golfer needs another eagle to win. Without waiting for him to say anything, the stranger quickly moves to his side and says, "Would winning this match be worth giving up the rest of your sex life?" "Definitely," the golfer replies, and he makes the eagle. As the golfer is walking to the club house, the stranger walks alongside him and says, "I haven't really been fair with you because you don't know who I am. I'm the Devil, and from this day forward you will have no sex life."

"Nice to meet you," the golfer replies, "I'm Father O'Malley."

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Denmark.

In Denmark they have a novel way of getting motorists to slow down – I think it would work here, it’s definitely worth a try – what do you think??

Have a look HERE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

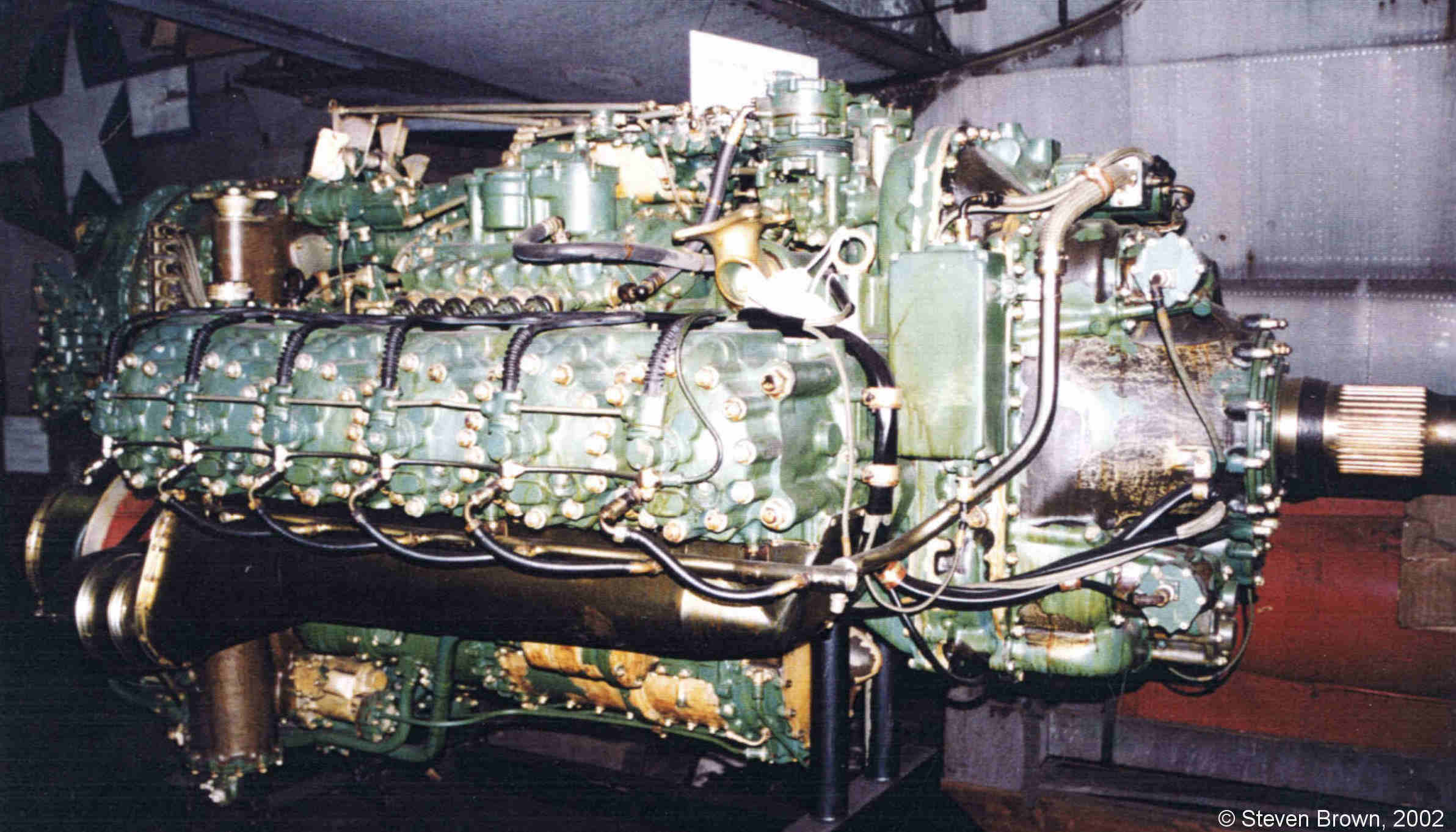

Napier Nomad Engine.

From the “Whatever happened to?” file.

In 1945 the UK Air Ministry asked for proposals for a new 6,000 horsepower (4,500 kW) class engine with good economy. Curtiss-Wright was designing an engine of this sort of power known as the Turbo-compound engine, but Sir Harry Ricardo, one of Britain's great engine designers, suggested that the most economical combination would be a similar design using a diesel two-stroke in place of Curtiss's petrol engine.

The advantages of such a design are obvious, no ignition problems and a fuel that is much less volatile than high octane petrol.

Before World War II, the UK engine manufacturer, Napier, had obtained a license to build the Junkers Jumo 204 diesel engine in the UK as the Napier Culverin engine, but the onset of the war made the Sabre engine more important and work on the Culverin was stopped. In response to the Air Ministry's 1945 requirements, Napier dusted off this work, combining two enlarged Culverins into an H-block similar to the Sabre, resulting in a massive 75-litre design. Markets for an engine of this size seemed limited, however, so instead they reverted to the original Sabre-like horizontally opposed 12 cylinder design, and the result was the Nomad.

Two versions of the engine were flight tested:

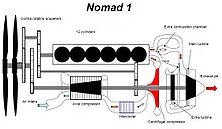

· The Nomad I diesel engine drove one of a pair of contra-rotating propellers with the Napier Naiad based turbine driving the other propeller as a turboprop and also supercharging the diesel unit.

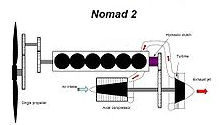

· The later Nomad II used the turbine to boost the manifold pressure of the diesel unit and was also coupled to the crankshaft, this version drove one propeller only. The resulting unit set the lowest specific fuel consumption figures seen up to that time, despite this the project was cancelled in 1955 after interest in the project had passed and £5.1 million had been spent on development.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nomad I

The initial Nomad design was incredibly complex, essentially two engines in one. One was a turbo-supercharged Diesel similar to the upper half of a Napier Sabre. Mounted below this was a complete turboprop engine, based on their Naiad design, the output of which was geared to a shaft driving the front propeller of a contra-rotating pair, the axial compressor also drove the supercharger impeller. As if that were not enough complexity, during takeoff additional fuel was injected into the rear turbine stage for more power, and turned off once the aircraft was cruising.

The compressor and turbine assemblies of the Nomad were tested during 1948, and the complete unit was run in October 1949. The prototype was installed in the nose of an Avro Lincoln heavy bomber for testing. It first flew in 1950 and appeared at the Farnborough Air Display on 10 September 1951. In total the Nomad I ran for just over 1,000 hours, and proved to be rather temperamental, but when running properly it could produce 3,000 horsepower (2,200 kW) and 320 lbf (1.4kN) thrust. It had a specific fuel consumption (SFC) of 0.36 lb/(hp·h) (0.22 kg/(kW·h)).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The engine was an attempt to provide the 1950s with a highly-economical, efficient aircraft engine for long-range operations. It was the only engine that used turbo-charging, supercharging and the turbo-compound principle.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The afterburner and intercooler have shunt ducting, so the engine can be run in a number of modes depending on power requirements. It resulted in a very fuel-efficient engine (163 g/bhp/hr) that produced 3,000 bhp plus 1.4 kN of thrust. However, it was difficult to get it to run well, so it never progressed beyond the prototype stage.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

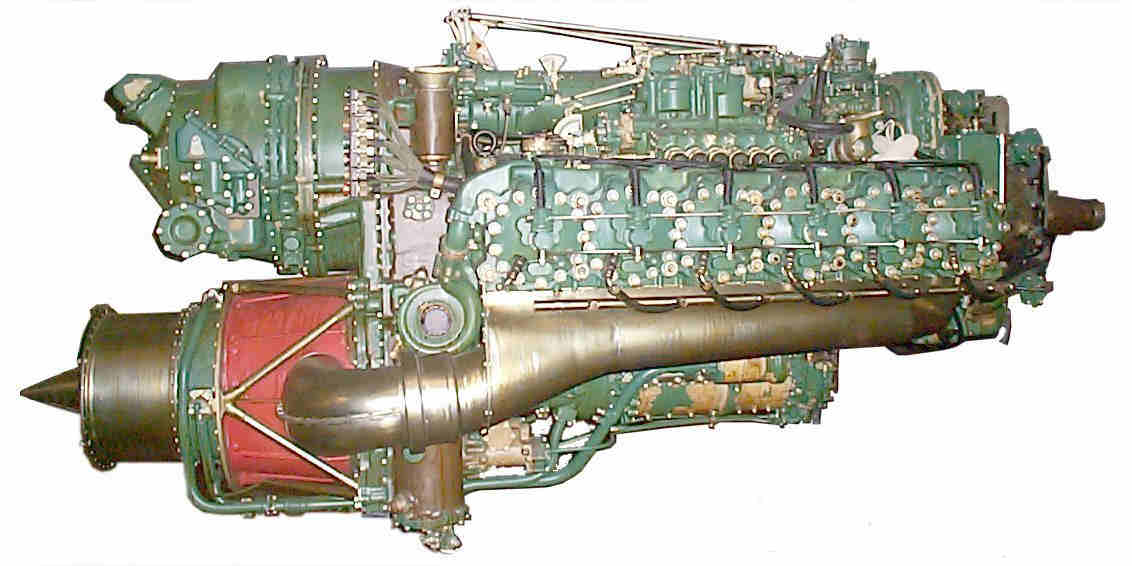

Nomad II

Even before the Nomad I was running, its successor, the Nomad II had already been designed. In this version an extra compressor stage was added, replacing the original supercharger. This stage was driven by an additional stage in the turbine, so the system was now more like a turbocharger and the compressed air for the Diesel was no longer "robbing" power for the turboprop. In addition the propeller shaft from the turbine was eliminated, and geared using a hydraulic clutch into the main shaft. The wet liners of the cylinders of the Nomad I were changed for dry liners.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The result was lighter, smaller and considerably simpler, a single engine driving a single propeller. Overall about 1,000lb was taken off the weight.

While the Nomad II was undergoing testing, a prototype Avro Shackleton was lent to Napier as a test-bed. The engine proved bulky, like the Nomad I before it, and in the meantime several dummy engines were used on the Shackleton for various tests.

By 1954 interest in the Nomad was waning, and after the only other project, and work on the engine was ended in April 1955, after an expenditure of £5.1 million.

Turbo-compounding was used on on several airplane engines after World War II, the Napier Nomad and the Wright R-3350 being examples. Turbo-compound versions of the Napier Deltic, Rolls-Royce Crecy, and Allison V-1710 were constructed but none was developed beyond the prototype stage. It was realized that in many cases the power produced by the simple turbine was approaching that of the enormously complex and maintenance-intensive piston engine to which it was attached. As a result, turbo-compound aero engines were soon supplanted by turboprop and turbojet engines.

Some modern heavy truck diesel manufacturers have incorporated turbo-compounding into their modern designs. Examples include: the Detroit Diesel DD15 engine that claims 5 percent better fuel economy with an additional 50 hp "free" compared to their previous engines, and Scania in production from 2001.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The B52 Bomber.

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is a long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber designed and built by Boeing and operated by the United States Air Force (USAF).

Beginning with the successful contract bid on 5 June 1946, the B-52

design evolved from a straight-wing aircraft powered by six turboprop

engines to the final prototype YB-52 with eight turbojet engines. The

aircraft

Although the B52, which replaced the Convair B-36, was built to carry nuclear weapons, and being a veteran of a number of wars, it has only ever dropped conventional munitions in combat. It carries up to 70,000 pounds (32,000 kg) of weapons.

They flew under the Strategic Air Command (SAC) until it was disestablished in 1992 and its aircraft absorbed into the Air Combat Command (ACC). This remained the case until February 2010 when it became part of Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). Superior performance at high subsonic speeds and relatively low operating costs have kept the B-52 in service despite the advent of later aircraft, including the Mach-3 North American XB-70 Valkyrie, the supersonic Rockwell B-1B Lancer, and the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit.

2005 marked the B-52's 50th anniversary of continuous service and you can see photos of the old BUFF (Big ugly fat fella) HERE.

B17

Speaking of aeroplanes, they reckon the B17, the main heavy bomber flown by the US during the Second World War, was as tough as an FC Holden ute. How some of them managed to limp home with bits missing from everywhere is still talked about when old aviators get together over a beer or two.

Click HERE to see some pics of one which did…

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward | |||||||||||||||||||||

determined to protect the Royal Navy and their fixed-wing carrier

capability at any cost. He set out to scupper the TSR-2 for the RAF,

thereby clearing the way for the RAF having to order the Buccaneer

(right), a vastly inferior aircraft in every sense. Mountbatten's

favourite habit was to slap down five photographs of the Buccaneer next

to one photograph of a TSR-2 and state 'Five of one or one of the other

at the same cost'. The vast difference in capability between the two

aircraft didn't seem to feature in this argument.

determined to protect the Royal Navy and their fixed-wing carrier

capability at any cost. He set out to scupper the TSR-2 for the RAF,

thereby clearing the way for the RAF having to order the Buccaneer

(right), a vastly inferior aircraft in every sense. Mountbatten's

favourite habit was to slap down five photographs of the Buccaneer next

to one photograph of a TSR-2 and state 'Five of one or one of the other

at the same cost'. The vast difference in capability between the two

aircraft didn't seem to feature in this argument.

first flew on 15 April 1952 with "Tex" Johnston as pilot. (

first flew on 15 April 1952 with "Tex" Johnston as pilot. (