|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links | Print this page |

||

|

My Story! |

||

|

MY STORY. Bill Dixon OAM

Early Neptune Days at No 11 Squadron.

Training and Graduation.

After I graduated from post-war No 1 Signallers’ Course in March 1951, I was fortunate to obtain a preferential posting to No 11 Squadron which had recently reformed at Pearce WA and which flew Lincolns, but was to be re-equipped with Lockheed P2V5 Neptune aircraft.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

The prospect of training in the USA and flying on these aircraft was a big enticement in nominating the preference. Also I had previously been posted to No 3 Telecommunications Unit at Pearce as a wireless telegraphist and had thoroughly enjoyed the posting.

I was fortunate to have been selected for the initial post-war signallers’ course. In many ways the course was a guinea pig course and the syllabus was very comprehensive. We started as members of No 4 Aircrew Course at No 1 Flying Training School, Point Cook in August 1949 and, in conjunction with trainee pilots and trainee navigators, completed the initial training course of the many varied aircrew and educational subjects.

From there we proceeded to Air and Ground Radio School (A&GRS) at Ballarat where we spent 1950. A feature of the course was that we were taught the same radio theory course as prospective wireless maintenance mechanics (later radio technicians). This instruction engendered a lifelong interest in electronics which his been of immense value ever since.

After completing an air gunner’s course at Air Armament School at East Sale in March 1951, we returned to Ballarat for our promotion to Sergeant and to receive our postings.

An event which has amused me

ever since occurred prior to our departure. We were busy getting our

clearances when somebody thought it would be a good idea if we had a

“wings” graduation parade. A call over the loudspeaker system instructed

all the trainees at the base to return to their quarters, change into

their

The station (base) commander, Wing Commander “Joe" Reynolds, appeared in order to present our wings. At that stage the sterling silver wings which Signallers later wore on drab uniforms were not available but the “wings” worn on the winter (blues) uniform were. When my name was called I marched out and Wing Commander Reynolds congratulated me and handed me my wing and said: “Congratulations sergeant. You have done very well. Here is your wing. I suppose you know that it is not regimental dress to wear it on your summer uniform”.

In later years I could not help contrasting this graduation parade with the many pilot graduation parades at Pearce which I attended when CO of No 25 Squadron!

|

||

|

We received the following list of faults and corrective measures from Roy Sharpe who reckons they were taken from RAAF 500’s many years ago. Back then, Pilots, being Sirs, wouldn’t or couldn’t or weren’t allowed to talk to the aeroplane fixers as they were Erks, so the Air Force came up with this wonderful little system where the Sirs would write little notes to the Erks about the bung bits in the aeroplane and the Erks would write little notes back to the Sirs when the bung bits were fixed. That way the Sirs could just ignore the Erks. The Sirs were good at writing these little notes, they’d write hundreds and hundreds of them, just to show the Erks that they were Sirs, and just in case some of these little notes got lost, the Air Force made the Sirs and the Erks write to each other in a book. The Air Force reckoned that as there was going to be heaps and heaps of notes they’d call the book the 500. They used to call it a 77, but the Sirs wrote heaps more notes than that, so they renamed it.

Here’s a few entries from the list.

S - Left inside main tyre almost needs replacement E - Almost replaced left inside main tyre.

|

||

|

No 11 Squadron

Sergeant ‘Nat’ Thompson was the other member of our course who was posted to No 11 Squadron. At that stage the first contingent of aircrew was in the United States for their Neptune conversion training. In order to keep the residual aircrew employed, the squadron had two Lincoln aircraft (A73-26 and A73-27) both of which were in a sad slate of repair and which required an extensive effort by the ground staff to keep either, or both, airworthy.

|

||

|

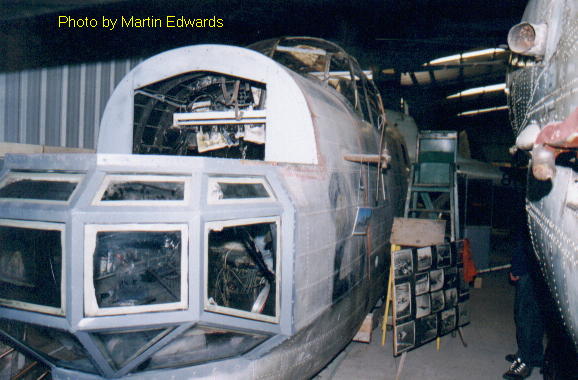

All that’s left of A73-27 today, the “front end” on display at the Camden (NSW) aircraft museum.

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

The aircraft situation improved remarkably when, in April 1951, the squadron was allotted a MK30 Lincoln (A73-58) direct from the production line at the Government Aircraft Factory (CAF) at Fishermen’s Bend, Melbourne.

This aircraft had the later version of the Merlin engines arid was much faster than earlier models. She was the “pride and joy” of the squadron until, unfortunately, she was allotted to No 82 (Bomber) Wing at Amberley.

|

||

|

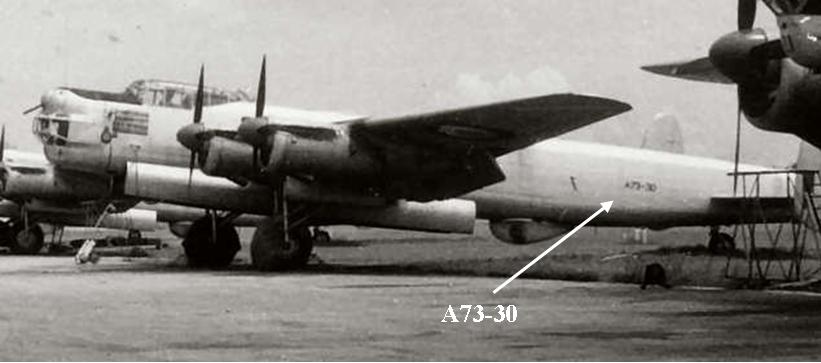

In return we collected A73-30, which had previously been a “Christmas Tree” (cannibalised for spares) and which required four engine changes before being reasonably airworthy enough to fly back to Pearce with an unserviceable automatic pilot.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

The interval between then and the arrival of the first Neptune was filled in with flying which was mainly devoted to keeping the pilots current. One diversion was a trip to Browse Island to "show the flag” to Indonesian fishermen who were reported to be fishing in Australian territorial waters. This was followed by a stay overnight at Broome where, the next morning, we had to manually refuel the aircraft from 44 gallon drums. (You were spoilt Bill – you should have spent time at 38Sqn – they thought pumping from 44’s was the norm – tb) I suspect the aircraft facilities at Broome have improved considerably since those days.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Neptunes at Last.

From memory, the first wave of Neptunes arrived in November 1951, however my first flight in these aircraft was on 6 December 1951 when, in A89-592, I logged I¾ hours for my only flight in the whole month. February 1952 saw my last flight in the old Lincoln, A73-31, after which training in the Neppies A89-592 and A89-595 (later re-designated A89-301 and A89-3O2) began. The subsequent build-up of the squadron began around this time. In addition to the return of the signallers who had trained in the first batch, the signaller’s section received an influx of ex-wartime warrant officers who had rejoined the RAAF and completed a refresher training course at Ballarat. Our signals leader was Squadron Leader Reg Heathcote who is fondly remembered by almost all of the signaller/AEO fraternity.

|

||

|

S - Test flight OK, except auto-land very rough. E - Auto-land not installed on this aircraft.

S - Something loose in cockpit E - Something tightened in cockpit

|

||

|

Training in the USA.

In May 1952, along with

other aircrew members, I was selected to go to the USA to receive further

training from the United Stales Naval Air Force. The signallers involved

were: Warrant Officer (later Squadron Leader) Alec

The flight from Sydney was in a DC6B Skymaster aircraft of British Commonwealth Pacific Airlines (BCPA). In those days the RAAF did not have the American style parachutes which the US Navy used and which were designed to be stored in special bays in the Neptune aircraft. Rather in an effort to save precious American dollars we had retained the old RAF style ‘chutes and these we had to carry with us as cabin baggage on our way to the USA in the civilian aircraft. I think there may have been a little consternation from the other (civilian) passengers when they saw a host of RAAF personnel come on hoard and make a great show of storing their personal parachutes on the aircraft!

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

In those days practically all of the aircraft crew of BCPA were ex RAAF and many of our contingent spent more time with the crew than with the other passengers.

|

||

|

S - Autopilot in altitude-hold mode produces a 200 feet per-minute descent. E - Cannot reproduce problem on ground.

S - Evidence of leak on right main landing gear. E - Evidence removed.

|

||

|

Aircraft in those days did

not have the range of modern machines so there were overnight stopovers at

the Mocambo Hotel at Nadi Airport in Fiji and at the Edgewater Hotel in

Honolulu before proceeding on to San

Our accommodation was in the Chief Petty Officers’ Mess at North Island. There were some difficulties associated with this arrangement. Chief Petty Officers in the USN were generally men with many years of service and, understandably, quite proud of their status. Also, in the USN, warrant officers held commissioned rank while sergeants were “consigned" to the sailor’s mess. I must confess that I had many queries from the old salts while the warrant officers in our group enjoyed the distinction of being mistaken for what the Americans call “bird” (i.e., full) colonels which was the equivalent of captain in the US Navy.

This situation was relieved somewhat on subsequent trips when I was a flight sergeant and the three stripes had a distinguishing crown above them and I no longer was quite so conspicuous.

After we finished our

training at North Island our aircraft were still not available from the

production line at Lockheed in Burbank, California so we had a brief trip

east to the US Naval Air Stations at Norfolk Virginia and Jacksonville,

Florida. From there we returned west and, together with the other aircrew

were quartered at the

However, on 17 September, 1952, we took delivery of a batch of aircraft from the Lockheed factory at Burbank and ferried them to the US NAS at Alameda, near San Francisco, prior to our departure on 29 September 1952 for Australia. Even with a (then) long range aircraft like the Neptune, we were obliged to have a stopover at Barber’s Point in Honolulu, a refuelling stop at a small coral atoll named Canton Island, a break at Nadi in Fiji, a further break at Richmond, and, eventually, we reached Pearce on 6 October 1952. En route to Richmond from Nadi we had flown over Sydney at the time of a fuel strike and we were amazed to be able to count physically the number of cars on Sydney Harbour Bridge.

|

||

|

S - Number 3 engine missing E - Engine found on right wing after brief search

S - Aircraft handles funny. E - Aircraft warned to straighten up, fly right, and be serious.

|

||

|

Return to the Squadron.

Shortly after our return, the conversion of the aircraft serial numbers to the A89- (300 series) must have commenced as my logbook shows an entry for A89-303 on 13 October l952.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

From that time onwards the tempo of activity stepped up considerably. There was much work to be done in converting more aircrew to aircraft type as well as further ferry flights to be made from the USA. The squadron was fortunate to gain quite a high calibre of aircrew and many of them continued long careers in the RAAF.

Among the Signallers' names I can recall are:

o Warrant Officer Alec “Junior” Bassett (right) who had an exchange posting to No 24 Squadron, RAF Transport Command, and later became a Squadron Leader and was on the staff at the Australian Joint Anti-Submarine School (AJASS) at Nowra.

o Warrant Officer Jim Beer who had been the chief technician at a Kalgoorlie radio station before re-enlistment. Jim later became a Wing Commander in the technical radio branch and was in charge of a radio installation party that installed new radio equipment throughout the RAAF.

o Flight Sergeant “Shorty” MacDonald who also became a Wing Commander in the technical radio branch Sergeant Jim Treadwell who later became a Wing Commander fighter pilot

o Sergeant Frank Howie who later became a Wing Commander in the technical armament area.

|

||

|

S - IFF inoperative. E - IFF always inoperative in OFF mode.

S - Suspected crack in windscreen. E - Suspect you're right. |

||

|

|

||

|

Among the pilots were:

o Flight Lieutenant Geoff Michael AFC who later became Air Commodore G.G. Michael AO OBE AFC (right) and was National President of the RAAF Association for many years and is now the Association’s first President of Honour.

o Flying Officer Gus Swinbourne who later had a successful career in civil aviation.

o Flight Sergeant Brian Dorrington who also had a successful career in civil aviation.

o Flying Officer “Jumpy Joe” Strickland who became a Squadron Leader Air Traffic Control Officer,

o Sergeant Geoff Lushey who had a very successful career in civil aviation and was a check captain.

|

||

|

S - Radar hums. E - Radar reprogrammed with words.

|

||

|

Among the navigators were:

o Flight Sergeant Bob Short who later had a successful career as a navigator in civil aviation.

o Sergeant Pete (Skeet”) Kennedy who later became a Group Captain.

In between ferry flights, I

was actively engaged in training signaller arrivals on the squadron and

also signallers who were on the Active Reserve in WA and who were attached

to the squadron for conversion to type and continuation training.

During this period there was an incident which later became known on the squadron as "The Oceania Roll”. Part of the training exercises for the squadron was to locate merchant shipping by radar, contact them by Aldis lamp, and then perform “Creeping Line Ahead” (CLA) searches in front of the ship in order to simulate a convoy escort exercise.

On this occasion the Oceania was an Italian liner which was intent on breaking the speed record to Australia. Our intention was to locate the Oceania by radar and any other shipping in the general area and conduct our normal type of exercise. We had no difficulty in locating the Oceania and a sergeant signaller (who shall remain nameless) and a sergeant navigator went to the rear of the aircraft in an attempt to contact the ship by Aldis lamp. When they reported that they were unable to get a reply the pilot made a couple of passes over the ship and we went on our way.

|

||

|

S - DME volume unbelievably loud. E - DME volume set to more believable level.

S - Friction locks cause throttle levers to stick. E - That's what they're there for!

|

||

|

When the aircraft returned

to Pearce there was a message for the crew to report to the flight

commander’s office. The flight commander, Flight Lieutenant “Paddy” Boyle

DFC, was extremely irate and demanded to know what we had been doing. It

appeared that he had received a message from the Fremantle Harbour

Paddy Boyle was not convinced that most of the crew were unaware of the incident. What the sequel was I do not know.

Squadron life continued to

be very much to my liking. Around May 1953, when there was news that the

squadron was to be moved to Richmond the following year, I became engaged

to my wife of now almost 55 years. Imagine the consternation when,

early one Monday morning, there was a message for Flight Lieutenant Geoff

Michael (pilot), Flight Lieutenant Ernie White (navigator), Pilot Officer

Don Ruediger (navigator), and Flight Sergeant Bill Dixon (signaller) to

report to the CO’s office. The CO, Wing Commander Dave Vernon, commenced

by saying: “Well!! We have had just about enough of you lot and we are

posting you all - to the United Kingdom that is” This was a time when my

we

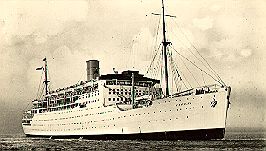

The CO noted my concern and asked me if I was about to be married. When he heard of my plans he contacted (then) Air Force Headquarters in Melbourne who advised me to continue with my wedding arrangements as my future bride would be booked on the ship (SS Strathnaver) with us all.

Thus ended the first of my most enjoyable three postings to No 11 Squadron, the third of which saw me, as the temporary CO of the Squadron, arrange for the disposal of those same Neptunes, and as the AEO Leader of the squadron, become involved with the training of AEOs on P3B Orion aircraft.

Bill is now semi-retired, living in Hobart and is the State Secretary of the RAAF Association, Tasmania Division.

|

||

|

A tour bus driver is driving with a bus load of seniors down a highway when he is tapped on the shoulder by a little old lady. She offers him a handful of peanuts, which he gratefully accepts. About 15 minutes later, she taps him on his shoulder again and she hands him another handful. She repeats this about five more times. When she is about to hand him another batch he asks her, 'Why don't you eat the peanuts yourself?'. 'We can't chew them because we've no teeth', she replied. The puzzled driver asks, 'Well, why do you buy them then?' The old lady replied, 'We just love the chocolate around them.' |

||

|

PS. The 44 gal drum, which

is 22.5 inches (572 mm) in diameter and 33.5 inches (851 mm) high,

(you can win money on

that - tb) resulted

The drums helped win the Battle of Guadalcanal in the first U.S. offensive in the South Pacific Theatre.

The U.S. Navy could not maintain control of the seas long enough to offload aviation fuel for U.S. aircraft ashore, so the drums were often transported to the island on fast ships such as destroyers, shoved over the sides, or time permitting, lowered in cargo nets. Aviation fuel is lighter than seawater, so the drums floated and Navy Seabees corralled the drums in small craft. |

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Forward

|

||

summer (drab) uniforms, and assemble on the parade ground.

summer (drab) uniforms, and assemble on the parade ground.

Bassett, Warrant Officer Keith (“Pappy”) Crookes, Warrant Officer Tommy

Ford, and me, Sergeant Bill Dixon.

Bassett, Warrant Officer Keith (“Pappy”) Crookes, Warrant Officer Tommy

Ford, and me, Sergeant Bill Dixon.

Francisco

and, eventually to the Naval Air Station at North Island. San Diego. Here

we completed courses on Anti-submarine Warfare and also courses on the

Neptune radar and Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) equipment.

Francisco

and, eventually to the Naval Air Station at North Island. San Diego. Here

we completed courses on Anti-submarine Warfare and also courses on the

Neptune radar and Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) equipment.  Country Club hotel in Los Angeles where we lived in luxury while waiting

for our aircraft to come off the production line. There were mixed

feelings among the group when we were advised that the Lockheed factory

was on strike and likely to be “out” for six weeks.

Country Club hotel in Los Angeles where we lived in luxury while waiting

for our aircraft to come off the production line. There were mixed

feelings among the group when we were advised that the Lockheed factory

was on strike and likely to be “out” for six weeks..jpg)

.jpg) Master who was lodging a complaint on behalf of the captain of the

Oceania. The captain had complained that a RAAF aircraft had circled the

Oceania flashed a light at the ship, and then dropped a message. The

captain had stopped his attempt on the speed record and had launched a

boat to collect the message. The crew located the object which had been

dropped and discovered it to be a roll of toilet paper!

Master who was lodging a complaint on behalf of the captain of the

Oceania. The captain had complained that a RAAF aircraft had circled the

Oceania flashed a light at the ship, and then dropped a message. The

captain had stopped his attempt on the speed record and had launched a

boat to collect the message. The crew located the object which had been

dropped and discovered it to be a roll of toilet paper! dding

date had been set for some six weeks’ hence.

dding

date had been set for some six weeks’ hence.  from military shipping requirements in World War II, the first

war in which trucks, cold rolled steel, stamp or pattern forging machinery

and welding were widely available.

from military shipping requirements in World War II, the first

war in which trucks, cold rolled steel, stamp or pattern forging machinery

and welding were widely available.